By Oleksandr Kachmar

Abstract

The rise of state-sponsored disinformation campaigns has exposed major vulnerabilities in modern Western national security doctrines. This paper aims to answer a question on how to effectively tackle Russian disinformation. This research conducts a comparative analysis of the tactics used by Russia by examining a Soviet-era campaign against the United States and a contemporary campaign against Ukraine. The study reveals that Russia has implemented similar disinformation tactics since the time of the Cold War to achieve its key objectives such as justifying the invasion of a sovereign state, creating disunity among NATO member states and partners, polarising Western societies and increasing the distrust towards governmental institutions among Western citizens. Further, the Ukrainian case study reveals the effectiveness of Russian disinformation and the failure of Western states to combat it. Therefore, findings demonstrate that in order to effectively combat Russian disinformation in the future, Western states should first recognise it as a substantial national security threat to increase defence spending, enhance international cooperation and attract more expertise to the domain. Most importantly, the Western world should shift its focus from technology-led solutions such as debunking, which has proved highly ineffective to humanities-based approaches such as educating society to effectively combat disinformation. A notable example of success in this area is Finland, where extensive media literacy programs starting at schools have significantly enhanced public resistance to disinformation. Lastly, the West should consider establishing an informational deterrence framework as a longer-term strategy.

Introduction

In recent decades the rising threats of hybrid warfare have become existential to the national security of the NATO member states. According to Chamayou (2015: 57) “the notion of a ‘zone of armed conflict’ should no longer be interpreted in a strictly geographic sense”. Therefore, western states can no longer rely on their long-standing security doctrines as various new threats cannot be countered through conventional military response or even diplomatic efforts. One of these emerging threats is a steep rise of disinformation that became a significantly more serious threat after the emergence of smartphones as the majority of the Western population is relying on the internet as a main source of news (McGeehan, 2018: 51). Furthermore, as the former UN Secretary-General Kofi Annan (2006) stated: “[t]here is no development without security”. Therefore, it is crucial for Western states not just to address emerging hybrid threats but also to develop an effective long-term strategy to combat them, guarantee prosperity, and prevent crises.

Russian Federation has a long historical practice of implementing disinformation as a tool in its broader foreign strategies in order to reach its objectives. The practice of the state using deception methods such as disinformation can be traced all the time back to the czarist secret police during the time of the Russian Empire and disinformation continued to be a crucial tool within the strategy of the KGB during the times of the USSR (Agursky, 1989: 13). Further, with the emergence of the technology and internet Russia was able to create an “extremely efficient asymmetric weapon” (McGeehan 2018: 51).

While the threat of disinformation is not a completely new topic and has been discussed in academia and among practitioners since the times of the Cold War the question of how to effectively combat disinformation, especially in the democratic context has become of the utmost importance for the NATO member states and partners. However, it can be argued that the response towards disinformation has not achieved the desired outcome to significantly minimize the Russian influence through disinformation in the Western states as according to Kirichenko (2024: 37) there are recent examples of how Russian disinformation campaigns can create a real advantage on the battlefield such as the campaigns directed at the US to “delay … aid to Ukraine”.

Therefore, in my research, I will critically analyze how Russia exploits its disinformation tactics to achieve its foreign strategic objectives and what states can do to combat Russian disinformation. In order to do so I will analyze two case studies of the Russian Federation and the former Soviet Union implementing disinformation in its foreign strategies and what impact did those have. Furthermore, I will analyze how NATO member states together with their partners tried to combat the Russian disinformation to understand what methods are the most effective and are most likely to significantly improve the security of the Western democracies in the long term from the threat of disinformation. My key arguments will be that in order to effectively combat disinformation Western states should first recognise it as a national security threat to open wider opportunities for countering this threat. Most importantly, instead of using ineffective technologies-led solutions such as debunking Western states should focus on humanities-based solutions that offer a whole-of-society approach that can be highly effective in combating Russian disinformation.

Literature Review

In order to understand how the Russian Federation implements disinformation and how to combat it further, we should first understand what scholars have mentioned about the topic in their research and, most importantly, what gaps exist in the current research.

In the literature regarding disinformation, scholars recognize that disinformation is quite a new topic that does not often have a fixed definition like older terms such as ‘lying’ and ‘misinformation’ (Fallis, 2009: 2). However, a common definition for disinformation would be information that is deceptive and “deliberately misleading” (Fallis, 2009: 5). It is crucial not to mistake disinformation for ‘misinformation’ that implies that “the source of the information made an honest mistake [while in disinformation the source] actually intended to deceive” (Fallis, 2009: 1). The author also highlights the importance of differentiating disinformation from simple ‘lying’ since “unlike lying, disinforming is always about deception at some level” (Fallis, 2009: 5-6). The author then presents six key variations of disinformation that are “Disinformation is usually taken to be a governmental or military activity; [it] is often the product of a carefully planned and technically sophisticated deceit; [It] does not always come directly from the organization or the individual that intends to deceive; Disinformation is often written or verbal information; [It] is often distributed very widely; The intended victim of the deception is usually a person or a group of people. But disinformation can also be targeted at a machine” (Fallis, 2009: 2- 3). Furthermore, the director of the Czechoslovakian Disinformation Department, Ladislav Bittman stated that disinformation is “a carefully constructed false message leaked into the opponent’s communication system to deceive the decision-making elite or the public [and] to succeed, every disinformation message must at least partially correspond to reality or generally accepted views” (Gioe and Brinkworth, 2024: 12). Therefore, we can observe that one of the main aspects of disinformation is an intent to deceive a certain group of people and in order for the deceive to be successful, it should be at least partially based on accepted beliefs or facts within the society.

Yet, before focusing on the disinformation campaigns launched by the Russian state we should first understand the overall concept of propaganda. One of the classics when it comes to the topic of propaganda can be considered Bernays Edward (1928: 9) who stated that the term propaganda, in fact, emerged after the creation by Pope Gregory XV of “The Office for the Propagation of the Faith (Congregatio de propaganda fide) [that] would supervise the Church’s missionary efforts in the New World … [and at the time the term was] [f]ar from denoting lies, half-truths, selective history or any of the other tricks that we associate with ‘propaganda’ now, that word meant, at first, the total opposite of such deceptions”. However, the perception of this term changed after the First World War when “[t]he minority has discovered a powerful help in influencing majorities” (Bernays, 1928: 47). Furthermore, Bernays (1928: 37) argues that the “conscious and intelligent manipulation of the organized habits and opinions of the masses is an important element in democratic society. Those who manipulate this unseen mechanism of society constitute an invisible government which is the true ruling power of our country”. Similarly, Bernays (1928: 48) further calls propaganda “the executive arm of the invisible government”. While in his focus author pays more attention to the internal use of propaganda we can observe that by this definition of propaganda as an executive arm of the invisible government the significant risk arises of what can happen if the invisible government is led by external forces. This is particularly crucial in recent years as the rise of the internet and social media opened an opportunity for those external forces to increase their influence in the invisible government often through implementing disinformation as an overall part of the propaganda strategy. Moreover, one of the most prominent voices on propaganda Harold Lasswell (1951: 71) emphasizes the importance of control over domestic information as if it will not be controlled the enemy will have a chance to create disunity within society.

Furthermore, disinformation comes in different formats, through different methods and the state of Russia implements various strategies for its influence campaigns involving disinformation. Kai Shu and Amrita Bhattacharjee (et al, 2020: 4) argue that “[d]isinformation can exist in different forms—false text, images, videos, and others. In addition, there are different ways by which false content can be generated—both by humans and machines or a combination of the two”. However, it is important to understand that the use of disinformation is not simply creating false and deceiving content, its focus is much broader and can be referred to the idea of Lukes (2005: 11) who introduced the concept of third-dimensional power that refers to shaping people’s “perceptions, cognitions, and preferences”. Furthermore, with the rise of Artificial Intelligence tools Russian disinformation has become even more frequent as evidenced by the fact that “Russian and Chinese influence campaigns using ChatGPT, and Al-enhanced disinformation campaigns [were] documented in 16 countries by Freedom House” (Gioe and Brinkworth, 2024: 15). One of the prevailing methods that Russian Federation uses as part of its broader disinformation strategy according to one of the ex-employees at a Russian state-run ‘troll factory’ is using bots and trolls to write “about 200 comments and 20 news posts for various fake pages each day [with specific teams] dedicated to the Ukrainian crisis and the US elections” (Splidsboel Hansen, 2017: 22). Moreover, as McGeehan (2018: 52) argues “between 9 percent and 15 percent of Twitter posts are already created by bots”. Furthermore, according to Splidsboel Hansen (2017: 23-24) one of the main goals of Russia in using methods such as bots is to create extreme perspectivism. The idea of extreme perspectivism can be especially well understood through the ideas of Nietzsche (2019: 13) who argued against the existence of any objective truth but focused rather on the variations of perspectives. Further, Russia implements this idea to make various versions of possible ‘truth’ in order to polarize the society or hide the Russian trace like in the case of the MH-17 flight wherethe “Russian state-controlled media … have offered at least nine different versions of what happened to MH-17 [none of those] correspond to the conclusion reached by the JIT [Joint Investigation Team]”(Splidsboel Hansen, 2017: 24). Moreover, according to Batiste (2020: 13), Russian state media uses influential speakers in the West in order to spread their narratives or just in order to create extreme perspectivism by inviting people such as “Holocaust denier[s]”. Using influential speakers in the West allows Russian state-controlled media to “boost the channel’s legitimacy” and the overall legitimacy of the narrative (Batiste, 2020: 13). Lastly, Kirichenko (2024: 37) revealed how Russian disinformation can create a real advantage on the battlefield on the case study of disinformation influencing “delays of US aid to Ukraine, which helped lead to the fall of Adviivka in February 2024” and the author calls Russian disinformation “low-risk and high reward strategy”.

Therefore, it is crucial to study Russian disinformation in order to understand what the further possible options there are to combat it. Furthermore, McGeehan (2018: 51) argues that “[b]y utilizing the internet as a direct conduit to individual Western citizens, Russia has created an extremely efficient asymmetric weapon”. By doing so Splidsboel Hansen (2017: 34) argues that “Russian media strategy seeks to exploit the vulnerabilities of liberal democratic media” such as the freedom of speech. Moreover, we can observe that the use of disinformation by the state of Russia will likely only grow as Chief of the Russian General Staff – Valery Gerasimov states “[t]he information space opens wide asymmetrical possibilities for reducing the fighting potential of the enemy” (McGeehan, 2018: 50). The reducing of fighting potential, furthermore, can refer to successfully spreading narratives to decrease morale among military personnel and to overall increase domestic distrust towards governmental institutions and polarize the society. Furthermore, McGeehan (2018: 50) argues that because in a “Western democracy, the people are the ultimate decision-makers. … Russia is attempting to offset Western technological superiority by going straight to the population and shaping their opinions in favor of Russian objectives”. This, therefore, reveals the significance of the threat behind disinformation, and as Thucydides stated, “a democracy could be manipulated by rhetoric to pursue actions not necessarily in its best interest” (McGeehan, 2018: 51).

Furthermore, today modern academics mainly look at two possible strategies to combat disinformation which are “technology-led; and humanities-based” (Gioe and Brinkworth, 2024: 19). The former, as Splidsboel Hansen (2017: 36) states can be based on “development of anti-disinformation algorithms” through the use of Artificial Intelligence that would be used by social media companies in order to prevent the spreading of disinformation. Moreover, Randolph Pherson and Penelope Mort Ranta (et al, 2020: 317) argue that with the rise of disinformation especially in the digital field effective strategies to combat disinformation can be: “Using third-party fact checkers to issue warnings of questionable postings; Creating a second, alternative and fact-based Internet; Establishing strict global screening protocols; Forming ‘safe spaces’ of validated information in the cloud”. Technology-led solutions, therefore, are viewed as a priority among many modern academics. On the other hand some academics like Livia Benkova (2018: 3) argue that the humanities-based approach might be more effective through educating the society in order for it to be “more resilient towards disinformation”. Furthermore, according to Shu and Bhattacharjee (et al, 2020: 13-15), the main way to combat disinformation can be done through educating society and promoting critical thinking, especially in individuals with cynical scepticism and a complete distrust towards the government often boosted by conspiracy theories.

However, modern academics tend to ignore other ways that were discussed more frequently among academics during the time of the Cold War. Therefore, as Cull and Gatov (2017: 33) state “Disinformation does not necessarily need to be fought purely with information tools. The threat of sanctions [against state spreading disinformation] can be a powerful way to retaliate against and curb disinformation”. Strategies like sanctions and other direct methods involving force are often overlooked by modern academics but are proven to be effective when the force against the state spreading disinformation is used wisely. Finally, current academics often fail to recognize that disinformation is not simple misinformation that occurred due to a mistake but a serious “national security challenge…” that must be treated as such in order to effectively tackle its effects (Gioe and Brinkworth, 2024: 10).

Methodology

In my research, I will implement the case study approach to understand the strategies used by Russia to spread disinformation to further advise the best possible ways to combat that hybrid threat. First, I will start by focusing on the case study of the disinformation campaign that was created by the Soviet Union which “alleged that the AIDS virus had been created by the U.S. government as a biological weapon” (Cull and Gatov 2017: 33). My second case study will focus on the disinformation campaign created by the modern Russian Federation that “accused Ukraine and the US at the UN security council of a plot to use migratory birds and bats to spread pathogens” (Borger and Rankin, 2022). Implementing the case study approach will allow me to compare the differences between the old disinformation strategies used by the USSR and look at how they differ from the strategies of the current Russia. Furthermore, it will allow me to observe the difference between the reaction towards disinformation campaigns by the NATO member states and partners and the overall effects and intentions of the disinformation campaigns. Therefore, that will allow us to observe what strategies can be the most effective in combating Russian disinformation.

Chapter 1: Active Measures, Maskirovka and Disinformation

The state of Russia has a long history of implementing disinformation as part of its foreign tactics that can be traced to the times of the Russian Empire when the Czarist Police practised “disinformation and forgery” (Agursky, 1989: 13). Furthermore, in order to understand Russian disinformation tactics it is crucial to explore the overall strategies of foreign influence used by the state and the role of informational warfare within it. The concepts of what Russia calls ‘Active Measures’ and ‘Maskirovka’ are highly important in understanding why the state of Russia through the years focused on developing and implementing its disinformation tactics in order to achieve its foreign strategic objectives.

Active Measures

Active measures or in the language of origin ‘Aktivnye meropriyatiya’ was a “term used by the Soviet Union (USSR) from the 1950s onward to describe a gamut of covert and deniable political influence and subversion operations, including (but not limited to) the establishment of front organizations, the backing of friendly political movements, the orchestration of domestic unrest and the spread of disinformation” (Galeotti, 2019). Further, the KGB saw active measures as an extremely effective tool in order to achieve its foreign strategic objectives by often weakening what was considered ‘hostile’ states. It was made clear by the chair of the KGB at the time – Yuri Andropov who in his Directive No. 0066 of 19821 wrote that the definition of ‘intelligence’ was “a secret form of political struggle which makes use of clandestine means and methods for acquiring secret information of interest and for carrying out active measures to exert influence on the adversary and weaken his political, economic, scientific and technical and military positions’” (Galeotti, 2019). The use of active measures decreased during 1990s after the Gorbachev’s reforms and during the first president of the Russian Federation Boris Yeltsin when the state made attempts to improve its relations with the West. However, under the Presidency of Vladimir Putin “Russia’s foreign intelligence services were restored to their old levels of funding and activity, and early hopes of a modus vivendi with the West soon foundered, hampered by unrealistic expectations and mutual suspicions” (Galeotti, 2019).

According to Pherson and Mort Ranta (2020: 323) one of the main goals of implementing active measures is to “manipulate the perceptions or actions of individual decisionmakers, the public, and governments to influence elections and the broader course of world events”. Therefore, in order to achieve the desired outcome through the active measures Russia uses a combination of governmental and nongovernmental bodies to implement active measures. Galeotti (2019) outlines the main conventional bodies that take part in those foreign influence operations that are the Russian Ministry of Foreign Affairs (MID), the state-controlled and dominated media, and multiple intelligence agencies such as The Foreign Intelligence Service (SVR), Military Intelligence (GRU) and Federal Security Service (FSB). However, in recent times Russia has significantly increased the use of other body which can be referred to as ‘Ad-hocrats’, in its broader active measures strategies that can refer to “[e]veryone—from business people to clergymen, students to scholars—[everyone who] can generate their own initiatives that would often be considered covert acts of subversion and disruption” (Galeotti, 2019). The latter one as we can observe proved extremely effective as it is much more complicated to spot and to prove Russian trace in the case of ‘ad-hocrats’ in comparison to official bodies such as the Foreign Ministry or the intelligence agencies.

Maskirovka

Further, the term ‘Maskirovka’ is a “complex Russian cultural phenomenon that defies easy definition” (Maier, 2016: iii). One of the main translations would be “something masked” (Ash, 2015) and the overall concept refers to Russian military deception. The concept of maskirovka for Russians according to Zimmer (2013) “was a viable weapon in protecting the Motherland. They had believed firmly in Sun Tzu’s centuries old contention that ‘all warfare is based on deception’”. Furthermore, Russian Maj Gen Alexander Vladimirov who is a vice-president of Russia’s Collegium of Military Experts while teaching the cadets about maskirovka stated that “As soon as man was born, he began to fight [and] [w]hen he began hunting, he had to paint himself different colours to avoid being eaten by a tiger. From that point on maskirovka was a part of his life. All human history can be portrayed as the history of deception” (Ash, 2015). This reveals that maskirovka for Russia is more than just a technique that the state implements as part of its covert influence tactics, it is “culturally rooted in Russian society and an important facet of Russian military operations” (Maier, 2016: iii). Therefore, maskirovka was used by the Russian state in various ways. In order to explain maskirovka Maj Gen Vladimirov describes the Battle of Kulikovo in 1380 when Muscovites 50,000 strong triumphed over Tatar-Mongolian who were 150,000 strong because of one regiment that hid in the forest and attacked “ferociously and unexpectedly and the ambushed Tatars ran away” (Ash, 2015). Therefore, the main goal of Russian military deception according to Maier (2016: 1) is “to conceal intentions, confuse adversaries, and misdirect enemy efforts in attempts to gain advantage”. However, while the element of surprise is an important part of maskirovka the application of this deception strategy in modern conflicts goes beyond a simple surprise strategy further “placing greater emphasis on creation of ambiguity, uncertainty, or for controlling responses of potential adversaries” (Maier, 2016: 1-2). Furthermore, “Maskirovka as Russian military science includes a broad set of principles, [such as] creating and maintaining a false reality for the enemy [and] concealing truth” (Maier, 2016: 5-6).

Overall, the Active Measures and Maskirovka are significantly intertwined as a part of Russian foreign influence strategies. While the former refers to deniable and covert political influence operations, the latter is used in both military tactics as the element of surprise and in the realm of informational space in order to create a false reality. Moreover, those concepts can be linked back to the idea of Bernays (1928: 37) about propaganda being the “invisible government”, as Russia directly tries to impose control on foreign ‘invisible governments’ through maskirovka and active measures. It is, therefore crucial to understand these terms if we want to study the phenomenon of Russian disinformation and create effective strategies on how to combat it.

Chapter 2: A case study of the Soviet Union AIDS disinformation campaign

While the history of disinformation can be traced back to the Czarist Russia, during the Soviet Union the use of those practices has increased significantly under the active measures. This case study reveals how the Soviet Union implemented disinformation in order to create international distrust towards the USA and also to decrease the trust of Americans towards their internal governmental institutions. Further, this case study uncovers one of the main purposes of the USSR using disinformation as part of its active measures which was to create disunity not only within the society of one state but also to create it on the global level between allied states. From the Soviet perspective creating this disunity was crucial as it viewed united Western states within NATO as a national security threat. Moreover, this case study demonstrates that the KGB did not just use the state media to spread the narrative but also valued any potential options to make a narrative more trustworthy by using media of other states so the narrative could finally reach its final destination – western media. Most importantly, this case study demonstrates a unique method of combating disinformation by tackling the problem at its source through the threat of sanctions rather than fighting it through technical solutions such as debunking which is one of the main Western strategies to combat Russian disinformation today.

Operation ‘Infektion’

Operation ‘Infektion’ otherwise known as Operation ‘Denver’ was as mentioned by Selvage and Nehring (2019) an active measures campaign done by the KGB during which the Soviet Union invested significant resources towards spreading the narrative that at the time, the new Human Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV) that causes Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndrome (AIDS) was spread because of the experiments conducted by pentagon that focused on genetical engineering. Today there are no doubts about the KGB’s involvement in this operation as even a former Russian Prime Minister and Director of Foreign Intelligence Yevgeny Primakov admitted years later the involvement of the Soviet intelligence (Kello, 2017: 215). Furthermore, the state has implemented a mix of actions in order to spread this narrative. First, the declassified Top-Secret document written by KGB officers Panayotov and Nikolov (1985) to Bulgarian state security reveals the ‘classic’ strategy implemented by the KGB to spread disinformation. As stated in the document to Bulgarian officials by the KGB “We are conducting a series of [active] measures in connection with the appearance in recent years in the USA of a new and dangerous disease, ‘Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndrome – AIDS’…, and its subsequent, large-scale spread to other countries, including those in Western Europe. The goal of these measures is to create a favorable opinion for us abroad that this disease is the result of secret experiments with a new type of biological weapon by the secret services of the USA and the Pentagon that spun out of control” (Panayotov and Nikolov, 1985). The document follows “… [i]t would be desirable if you could join in the implementation of these measures through your capabilities in party, parliamentary, public-policy and journalistic circles in Western and developing countries by promoting the following theses in the bourgeois press” (Panayotov and Nikolov, 1985). Therefore, from this document, we can observe that one of the most crucial factors for the disinformation campaign to be successful in the view of Soviet intelligence officers was to gain as much international credit for the story as possible in order for it to become more trustworthy. The ultimate goal here is for the narrative to reach the ‘bourgeois’ press.

The operation started in 1983 when an Indian newspaper, that was closely associated with Soviet intelligence services, published a story that blamed the US government for developing the new dangerous disease (Cull and Gatov, 2017: 33). Two years later the Soviet magazine called ‘Literaturnaya Gazeta’ reinforced the narrative from Indian newspaper that AIDS was created by the United States to serve as a biological weapon. Another declassified document from The Ministry of State Security (MfS) of East Germany (GDR) to the Ministry of the Interior (MOI) of the People’s Republic of Bulgaria (Anonymous, 1986) states “With the goal of exposing the dangers to mankind arising from the research, production, and use of biological weapons, and also in order to strengthen anti-American sentiments in the world and to spark domestic political controversies in the USA, the GDR side will deliver a scientific study and other materials that prove that AIDS originated in the USA, not in Africa, and that AIDS is a product of the USA’s bioweapons research”. We can observe once again the main intention behind the disinformation campaign which is to create both domestic and international distrust towards the USA and its institutions. Furthermore, following the joint efforts of the KGB, and its partner intelligence services like those of Bulgaria and East Germany (GDR) together with promoting narrative in countries less associated with Soviet influence such as India, the narrative has successfully spread to a large extent. That is further demonstrated in another letter written by the KGB to Bulgarian State Secretary (Anonymous, 1987) that states “As a result of our joint efforts, it was possible to widely disseminate this version. Independent of us, it was picked up by a number of bourgeois newspapers, in particular, the English ‘Sunday Express’, which gave it additional credibility and authority. The articles and brochures of Jacob Segal, a professor at the Humboldt Institute at a Berlin university attained great renown. The aforementioned version gained considerable resonance in African countries, which have persistently rejected as racist the theory propagated by the Americans that the AIDS virus originated in African green monkeys”. Further,this reveals that from the perspective of the Soviet Union, the operation can be considered reasonably successful when it has reached the Western media. This again can be explained by the fact that as we could observe in the previous two letters the main goal of the disinformation campaign was to create disunity within American society and on the global level among NATO partners. Furthermore, to create this distrust a story coming from the domestic Western sphere media was viewed as the most effective by the Soviet intelligence.

US Countering Soviet Disinformation

In 1987 after the narrative started to appear in Western media it started to do some harm for the United States both internationally and domestically. Furthermore, the method which the US has implemented in order to combat these disinformation tactics is far from the common methods that are used today to tackle disinformation such as fact-checkers and debunking. According to Cull and Gatov (2017: 34-35) in 1987 when the stories started to have a real negative impact on the US, its government decided to tackle “the problem at its source”. In April of that year Health and Human Services (HHS) Assistant Secretary Robert Windom and Surgeon General C. Everett Koop during the joint US-USSR Joint Health Committee showed the deep dissatisfaction of the Soviet Union to “use a grave international public health problem for base propaganda purposes” (Cull and Gatov, 2017: 34-35). Following that in 1988 Everett Koop informed his counterparts from the Soviet Union that the United States would stop all supply of the scientific information needed to fight the AIDS epidemic if the disinformation campaign did not stop. After that according to Herbert Romerstein who was director of the Office to Counter Soviet Disinformation at the U.S. Information Agency, “The effect was as if a faucet had been turned off [and] suddenly the stories practically disappeared” (Cull and Gatov, 2017: 34-35). Therefore, that reveals a very unique case of fighting disinformation. In contrast with widely used modern methods such as debunking and fact-checkers, the US has ended the campaign by tackling the problem at its source through the threat of sanctions. Most importantly, this implies that during those times the United States viewed disinformation as a significant national security threat that affected the policymakers to implement one of the conventional responses to national security threats which is the threat of sanctions to stop all scientific information sharing with the USSR.

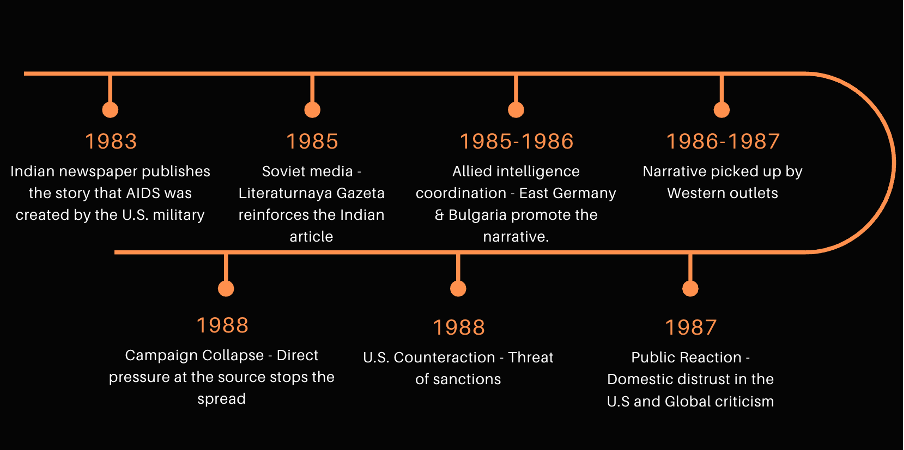

Illustration 1 presented below demonstrates the timeline of how the narrative travelled

In conclusion this case study demonstrates one of the most common strategies that the KGB used to spread disinformation. In their view for the active measures campaign focusing on creating distrust among domestic and international audiences to be successful, the end goal was for the information to get to the Western audience through their domestic sources. Furthermore, in order to do that the Soviet Union would use various allied intelligence services and media of other countries to portray the narrative as more valid and trustworthy. Moreover, this case reveals how, what today some may consider unorthodox methods to fight disinformation, can be effective in certain cases. The direct dialogue with the country-source of disinformation and the threat of sanctions might be an extremely effective method to fight disinformation in some circumstances as can be observed from that particular case.

Chapter 3: Recycling the narrative – Case study of Ukraine and Georgia

Following the collapse of the Soviet Union, the start of Vladimir Putin’s presidency, and the rise of the internet and social media Russian Federation increased its focus on the disinformation campaigns as part of its active measures strategy. The tactics used by Russia of blaming other governments for secretly developing biological weapons did not stop. On the contrary, the Russian Federation started to use it more frequently towards the states of the former Soviet Union such as Georgia and Ukraine. This chapter, while briefly describes the case of disinformation in Georgia, will predominantly focus on the disinformation campaign that Russia has launched towards Ukraine. The campaign has been blaming Ukraine for the development of biological weapons through the help of the US since 2016 but intensified prior to the full-scale Russian invasion of Ukraine. The case study used in this chapter will demonstrate how Russia has ‘recycled’ the narrative that it used during Operation ‘Infektion’ and how those tactics differ from the ones implemented during the former Soviet Union. Most importantly, this case study will reveal a step-by-step process of how the narrative travelled, where it emerged and what were the intentions behind it. It is crucial to view the disinformation that Russia uses as part of its active measures not just through the technical lens but through analyzing the intent of the state or in other words what they want to achieve with it. Finally, the chapter will analyze to what extent the attempts to combat this campaign were successful and what strategies were used to do so.

Russian Disinformation in Georgia

Soon after the Russian invasion of Georgia in 2008, Russia launched a disinformation campaign blaming the Georgian government and the Pentagon for “establishing a chain of bio-weapons labs on its borders. At the heart of the accusations [was] the Richard Lugar Center for Public Health Research in the Republic of Georgia” (Lentzos, 2018). The Richard Lugar Center after opening became one of the most advanced centers in the whole country when it came to diagnostic capacity and was the “first high-containment laboratory in the region” (Lentzos, 2018). Following the statements by the Russian Federation, a group of international experts arrived to assess all activities and areas at the center and interview the personnel. Further, after the assessment was finished the group of international experts concluded that “the Center demonstrates significant transparency” (Lentzos, 2018). This short case, while will not be the key focus of the chapter, is crucial to understand the disinformation tactics Russia uses as part of its active measures. Launching a campaign blaming the state which was just invaded by Russia for secret biological developments that would pose a threat to Russian national security is a common tactic used by the state to justify the reason for the invasion. That will be even further demonstrated in the example when Russia blamed Ukraine for developing biological weapons that echo various tactics used from the Georgian case study and even operation ‘Infektion’.

Russian Disinformation in Ukraine

One of the first mentions that Ukraine might be developing biological weapons with the help of the United States emerged in 2016 when Russia Today (Anonymous, 2016) published a statement by the Former head of Rospotrebnadzor (Russian national public health agency) Gennady Onishchenko who said that “US may be deliberately infecting mosquitoes with Zika virus [in Ukrainian biolabs]”. Similarly to the Georgian case, the main target of that disinformation campaign were laboratories of the Ukrainian Ministry of Health that were engaged in scientific research both domestically and internationally and had assistance from the US government (Selvage, 2022). Moreover, the Kremlin has stated that the ’bioweapons’ research in Ukraine “represents a threat to Russia” (Selvage, 2022). The main threat according to Moscow was that Ukraine was developing dangerous pathogens that could be spread free along the border between Ukraine and the Russian Federation. This narrative would appear from time to time on Russian media state channels, however, it was not highly promoted before the full-scale invasion. Further, on February 24, 2022, the narrative intensified significantly as could be seen from the “hashtag #USBiolabs [that] started to trend on Twitter as dozens of accounts repeated a piece of Russian propaganda, claiming that the actual focus of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine was secret U.S. biolabs where deadly diseases … were supposedly being produced” (Evon, 2022). The China’s Foreign Ministry has further helped to spread the narrative by “repeating the Russian claim several times and calling for an investigation” (Rising, 2022). Following that, after several weeks in March same year during the UN Security Council Russian permanent representative to the UN, Vasily Nebenzya claimed that Ukraine with the help of the United States government created biological weapons that would be spread by the migratory birds alongside bats and insects in order to spread disease on the Russian territory (Borger and Rankin et al, 2022). Further, Nebenzya tried to portray this ‘threat’ not just as a threat to Russian national security but to the collective European security as he stated “We call upon you to think about a very real biological danger to the people in European countries, which can result from an uncontrolled spread of bio agents from Ukraine … And if there is a such a scenario then all Europe will be covered” (Borger and Rankin et al, 2022). The claim was followed by the statement of the Russian foreign minister Sergei Lavrov who has elaborated even further and called the biological weapon “ethnically targeted” (Borger and Rankin et al, 2022).

Following those statements, the United Nations, various Western states and Ukraine have debunked and denied this story. The UN’s high representative for disarmament, Izumi Nakamitsu, claimed that the United Nations was “not aware of any biological weapons programmes [in Ukraine]” (Borger and Rankin et al, 2022). Furthermore, Ambassador Linda Thomas-Greenfield (2022), the U.S. Representative to the United Nations, stated: “There are no Ukrainian biological weapons laboratories supported by the United States. Ukraine does own and operate a public health laboratory infrastructure, as do many countries that seek to guard themselves from infectious diseases. These facilities make it possible to detect and diagnose diseases”. Moreover, The Security Service of Ukraine (SBU) has denied any kind of involvement of the state in the development of biological weapons since 2020 (Evon, 2022). However, despite the lack of evidence in the UN, denial and debunking by Ukraine and the US of the idea that a simple health laboratory supported by the US government was not developing biological weapons appeared to be not enough to stop the spread of the narrative. The study by Brandt and Wirtschafter (et al, 2022) analyzing the spread of Russian disinformation about the US funding the bioweapons development in Ukraine, revealed that out of Apple’s Top 100 American podcasts episodes aired between 8-18 March, 30 repeated the false claim, with 27 supporting it and three presenting it neutrally.

Intentions Behind Russian Disinformation

This case study, furthermore, reveals Russian intentions behind using this disinformation tactic as part of its active measures strategy. The intentions can be split further into the two most crucial ones – justify the invasion and polarize the Western hemisphere while increasing distrust towards governmental institutions. The first intention to justify the reason for the invasion is done for various reasons such as keeping the support for the so-called ‘Special Military Operation’ (Spetsialnaya Voennaya Operatsiya – SVO) back home among domestic audiences. Further, it is crucial for the state to justify the reasons for the invasion to try to preserve its image in the international arena and try to convince other nations to support Russia or at least stay neutral in the UN votes regarding the Russo-Ukrainian war which as we can observe was partially successful with certain countries from the Global South. Moreover, apart from justifying reasons for the invasion to keep support among domestic audiences and try to preserve the political image in the international arena, the second intention behind this tactic is to further disunite the Western hemisphere both politically and on the societal level by polarizing it even further. The intent behind creating political disunity can be seen in the statements presented above by Nebenzya about biological weapons being a threat not only to Russia but to the whole of Europe. From the Russian perspective, it had to undermine European support towards Ukraine and raise concerns among European nations about its biggest NATO ally the United States participating in clandestine projects that are against the Biological Weapons Convention. Further, the intent to polarize Western society even further can be seen in the fact that the narrative together with the hashtag #USBiolabs was significantly pushed on X (former Twitter) during the first few weeks of full-scale invasion (Evon, 2022). Lastly, after the narrative achieved its final audience through American podcasts, the majority of which supported the narrative, it had to further polarize the US and overall Western society and most importantly create a distrust among US citizens towards its governmental institutions.

Comparing Soviet and Russian Disinformation Tactics

Furthermore, when comparing the disinformation tactics used by the Russian Federation in the Ukrainian scenario to the ones used during Operation ‘Infektion’ we can observe several key similarities. The first similarity is methodology. In both cases, Russian intelligence services highly value any foreign support from its partner nations in order to portray the narrative as more trustworthy. Further, increasing the credibility of the story is crucial from the Russian perspective in order for it to reach its final audience which would be considered Western citizens and politicians. Most importantly, it can be argued that the intent in all the disinformation tactics from Operation ‘Infektion’ to campaign in Georgia and following in Ukraine is very similar. The main intention is either to justify Russian military invasions or to polarize Western society on both political and societal levels by creating distrust in-between allied NATO nations, and towards domestic governmental institutions by Western citizens. As demonstrated by the above case studies, the disinformation campaign will always have at least one of those objectives and in some, it will be a blend of both as can be seen in the case study of the disinformation campaign towards Ukraine. However, while methodology and intentions arguably stayed extremely similar, the main difference in comparison with successfully implementing disinformation during the times of the Soviet Union and today is the difficulty of reaching the final audience. As can be seen, in the first case study KGB invested extremely significant time and resources in spreading this narrative by actively collaborating with foreign intelligence agencies and even starting the campaign outside of Soviet state media in an Indian newspaper. And even after those hard efforts it took several years for the story to be repeated by the Western media and to cause damage. In the case of the campaign towards Ukraine to reach the final audience became much simpler. First, the state made less effort to distance itself from the story as it started in the Russian state-sponsored media in contrast with the Soviet narrative that started in foreign media outlet. Furthermore, after the intensification of the narrative following the 2022 full-scale invasion, it took less than a month for the narrative to appear in 30 American Top-100 podcasts with 27 supporting the narrative (Brandt and Wirtschafter, et al, 2022). This reveals, that mainly because of the rise of the internet, social media and ‘alternative media’ such as podcasts, spreading the disinformation narrative does not anymore require as much effort as was required during the Soviet Union. Furthermore, it can be argued that Valery Gerasimov, Chief of the Russian General Staff is right when he calls disinformation an asymmetrical weapon with wide possibilities “for reducing the fighting potential of the enemy” (McGeehan, 2018: 50). This can be demonstrated by the fact that through this and other similar disinformation campaigns, Russia was partially successful in raising scepticism among the American voters about supporting Ukraine as demonstrated in the study done by the Pew Research Center (Wike and Fagan, 2024) which reveals that a number of American public agreeing that the US is providing too much support for Ukraine has grown from just 7% in start of March 2022 up to 31% in November 2023. While the growth in that data cannot be purely contributed to the success of Russian disinformation tactics it can be argued that their impact has still played a significant role in influencing this increase.

West’s Failure to Combat Russian Informational Influence

Further, when observing what methods were used by the states under attack in order to counter those disinformation tactics it can be argued that those countermeasures were not successful to a large extent. While at the time of implementation in March 2022, Russian disinformation tactics did not immediately succeed in creating disunity among NATO member states, more polarization between Europe and the USA can be seen following the victory of Donald Trump during the last election especially since some of Trump’s elects such as the Director of US National Intelligence Tulsi Gabbard endorsed in the past “Russia’s main justifications for invading Ukraine: the existence of dozens of U.S.-funded Biolabs working on some of the world’s nastiest pathogens” (Klepper and KnickMeyer, 2024). Furthermore, the fact that the narrative got to almost a third of Top-100 American podcasts most of which supported the narrative reveals that strategies implemented by the US, Ukraine and the United Nations of debunking the story and stating that there is no evidence to support it is not enough to counter the effects by the disinformation tactics especially in the long term as the story was still repeated not just among US citizens but even the highest ranking officials in current Trump’s administration.

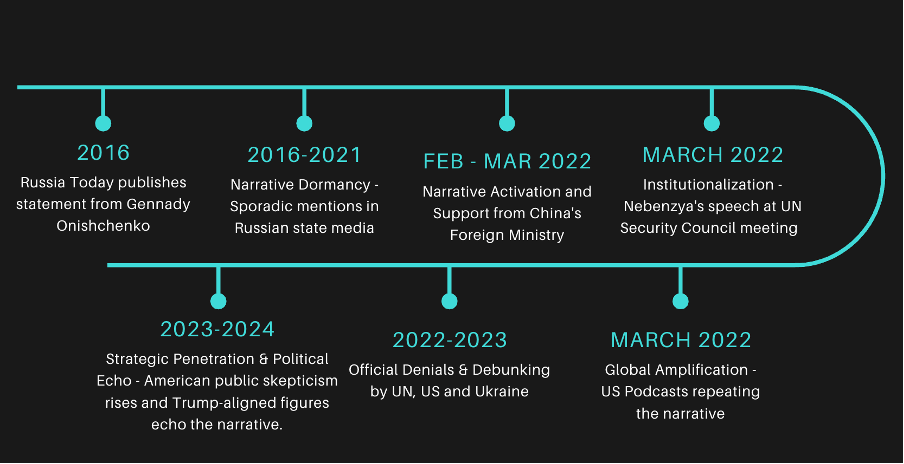

Illustration 2 presented below demonstrates the timeline of how the narrative emerged and travelled to its final audience.

In conclusion, we can observe that the strategy of the Russian Federation blaming foreign governments, especially those of the former Soviet Union, for developing biological weapons that pose a threat to Russian national security is not a new strategy but rather a ‘recycled’ one as can be seen from the previous chapter’s case study. The main intentions behind the narrative can be justifying the invasion or creating disunity among NATO member states and partners, polarising Western societies and increasing the distrust towards governmental institutions among Western citizens. Moreover, in contrast with similar types of operations conducted during the time of the Soviet Union, for the modern Russian Federation successfully spreading the narrative to the Western audience, became much more effortless and convenient due to the rise of the internet, social media and the alternative media such as podcasts. Finally, when it comes to countering the narrative the current strategies implemented by the Western states such as debunking proved to be highly ineffective. That can be implied by the fact that the narrative was supported among dozens of Top-100 American podcasts in March 2022 and even repeated by today’s US Director of National Intelligence. Therefore, those factors have undoubtedly contributed towards creating a certain degree of disunity among NATO member states and increased distrust towards domestic governmental institutions by the American public followed by a greater scepticism towards support for Ukraine. This once again proves that disinformation can truly be a dangerous asymmetrical weapon especially when in the hands of the state that is ready to allocate a significant amount of resources and expertise to it. We shall, furthermore, examine what strategies to combat this asymmetrical weapon can Western states implement in the next chapter.

Chapter 4: Combating Russian Disinformation

Now when we can understand the main intentions behind the Russian disinformation campaigns that have stayed quite similar since the Cold War up until this day, we should answer the most crucial question of what the Western states can do to combat Russian disinformation successfully. This chapter will consist of several key arguments for how Western states can combat this new threat. The first argument is that it is crucial to recognise disinformation as a national security threat, not just a minor inconvenience as it can have a serious impact on the society and the ability of the state to defend itself. The second argument is that many NATO member states and their partners overestimate the effectiveness of technology-led solutions and should instead prioritise humanities-based solutions such as educating society that proved to be effective to a large extent in the example of Finland. Lastly, NATO states together with partners can develop disinformation deterrence tools that would prevent hostile states like the Russian Federation from using it in such significant capacities, but this approach is complex and would require studying the possibility of applying it further.

Yet, before looking at strategies to combat disinformation we should first acknowledge that it is an extremely difficult task. Firstly, disinformation itself in the social media and internet age is relatively a new threat that is much more complex to combat since it does not have clear geographic limitations and is quite complicated to trace in some cases to the original source. Moreover, the task of combating disinformation becomes even more complex in Western reality since many states are limited in the choice of possible solutions due to the limits of democratic values and free speech. Therefore, effectively combating disinformation while preserving free speech and adhering to democratic values is a unique challenge that will not be easy to overcome.

Disinformation – National Security Threat

Looking back to the ideas of Bernays (1928: 37) who argued that propaganda is a part of the “invisible government”, the cases presented above reveal the real dangers of what can happen if this invisible government is even partially controlled by the external forces. The widespread debunking did not prevent Russia from successfully spreading the narrative about the US and Ukraine participating in developing biological weapons as can be seen by the fact that a high number of podcasts have sympathized with the claim and portrayed it as trustworthy. Moreover, the repetition of the claim by high-ranking US officials from the intelligence community reveals that keeping the sovereignty of the invisible government is a crucial task for any state that wants to maintain security and ensure prosperity. Furthermore, it is of the utmost importance for the approach to combat disinformation to be systematic among NATO allies and its partners. So far, certain states have taken steps to make a systematic response towards Russian informational influence and create various anti-disinformation agencies or ministries. An example could be the United Kingdom which created the Counter-Disinformation Units as a part of “the British Army’s 77th Brigade” (Gioe and Brinkworth, et al 2024: 17). However, this is still not a common practice in the West as disinformation is currently not being treated as a significant national security threat by many states. Moreover, even creating anti-disinformation units within the army is arguably not the most effective response to combat the problem of disinformation as “these are small units within the government for a persistent society-wide threat, and more problematically, they are security agency-focused developments” (Gioe and Brinkworth, et al 2024: 17). This brings us to a crucial point. In order to successfully combat Russian disinformation Western states should first acknowledge it as a national security threat. Not so long ago NATO declared cyberspace as a new operational domain in which certain actions can be treated as a declaration of war and even trigger Article 5 (Pearson and Landay, 2022). Therefore, this reveals that NATO has already an existing framework for acknowledging non-kinetic operations as significant national security threats. Furthermore, declaring informational space as another operational domain will open an opportunity to increase defence spending allocated specifically to tackling disinformation. Defence budgets should not be overlooked and are crucial when it comes to tackling any kind of national security threat as war in any space whether kinetic or non-kinetic is a war of economies. Further, the nominal GDP of Russia is approximately the same as the GDP of Italy, only one NATO member state. The difference, however, lies in the fact that the Russian Federation is ready to invest a significant amount of resources and expertise towards the weaponisation of information. NATO member states together with their partners, therefore, would not face any problem of increasing defence spending towards tackling disinformation to much higher levels than the one of modern Russia due to significant economic advantage. That would allow countries to continue developing new and effective countering strategies by attracting more expertise to the issue. Moreover, recognising disinformation as a national security threat will likely increase the cooperation between the NATO member states and partners, which is highly crucial as tackling threats without strict geographical boundaries and in an increasingly globalized world is extremely complicated without extensive international cooperation between the states.

Combating Disinformation Through Education

Further, to effectively combat Russian disinformation Western states should shift their focus from technology-led solutions to humanities-based (Gioe and Brinkworth, 2024: 19). Lately, one of the key strategies of many states was creating various debunking platforms like the EU establishing East Stratcom Task Force (Splidsboel Hansen, 2017: 23). While the debunking should remain a part of tackling disinformation according to Splidsboel Hansen (2017: 35) “It is not, however, to be considered a systemic response. For that it is too patchy”. Furthermore, the case study of Ukraine reveals that the effectiveness of debunking is highly overestimated and should be a complementary part of combating disinformation rather than the central part of it. Therefore, Western states should shift their focus towards more effective methods that are humanities-based. According to Benkova (2018: 3) one of the most effective methods to combat disinformation is to educate the society and “improve [its] media literacy”. Further, according to Gioe and Brinkworth (et al, 2024: 17), “the whole-of-government and even whole-of-society approach is the only path forward [to combat disinformation]”. Therefore, while strategies such as debunking might help, creating a resilient society is arguably one of the most effective methods to combat disinformation, especially in a democratic context where simple banning of all media supporting foreign narratives is not an option due to the freedom of speech and democratic values. Moreover, one of the most prominent examples of a country that successfully combated the influence of Russian disinformation while upholding its democratic values is Finland. As Henley (2020) stated, “With democracies around the world threatened by the seemingly unstoppable onslaught of false information, Finland – recently rated Europe’s most resistant nation to fake news”. What is interesting, this high rating of Finland was achieved without banning any Russian state-sponsored media. The effectiveness of Finland’s strategy lies not in the technological-led solution such as debunking but in humanities-based solutions – educating the society about the informational threats which Finland started to do from the primary schools (Henley, 2020). Kivinen who is a head teacher in the school of Helsinki stated that the main reason for teaching children informational literacy is to develop “active, responsible citizens and voters [who will be well-versed in] Thinking critically, factchecking, interpreting and evaluating all the information [they] receive, wherever it appears” (Henley, 2020). This approach as can we observe resulted in Finland being ranked among countries with the highest resilience towards disinformation. Most importantly the country was able to achieve this result without sacrificing its democratic values.

Informational Deterrence Framework

Lastly, another solution that might be effective in helping Western states tackle the invasion of their invisible governments by external powers like Russia is what Cull and Gatov (2017: 34) call tackling “the problem at its source”. An example can be seen in the first case study when the United States has significantly decreased the amount of disinformation directed towards it by threatening Soviet Union with sanction. This, while not something that would be considered a conventional response among academics should not be overlooked as going directly to the state source of the disinformation, as revealed in the first case study, can be helpful in certain cases. This idea can be further elaborated as a deterrence tool in informational space. While it would be extremely complicated for the Western states to mirror the scale of disinformation in Russia due to its closed media environment, Western states can use the threat of sanctions as a deterrence mechanism. Therefore, as an example deterrence could work as follows. Considering the disinformation has already been declared a national security threat if a Western state finds substantial evidence for a hostile state like Russia investing in the spread of disinformation in the country’s domestic informational space, that would trigger deterrence mechanisms like swift implementation of significant economic sanctions towards Russia and other sanctions on affiliated parties that willingly assisted hostile state spreading disinformation. This could arguably create a deterrence mechanism that could prevent disinformation on a large scale as Russia would have to construct its active measures much more carefully to make the process of finding evidence more complicated. This, therefore, could decrease the amount of disinformation as in this scenario it would feel more like walking on a minefield, rather than walking in the park which Russia is arguably doing at the moment. However, it should be noted that this method cannot promise high effectiveness as it used to do during the times of Cold War since the rise of the internet and overall lack of control over informational space in comparison to last century even by states like Russia. Therefore, while this method may still be an effective tool in some particular scenarios, achieving the effect “as if a faucet had been turned off” after the threat of sanction may be more complicated due to the uncontrollable nature of the internet and social media (Cull and Gatov, 2017: 34-35). Furthermore, the idea of informational deterrence is something that can be studied further as a long-term method to deter the spread of disinformation.

In summary, we can observe that for the democratic government to impose control over its invisible government or in other words informational space it is crucial to implement the right strategies that will preserve freedom of speech but at the same time limit the influence of this asymmetrical weapon implemented by Russia. The approach to combating disinformation is a complex one which requires combined effort not just from security agencies but from the whole of society. Therefore, to increase resilience towards the disinformation the Western states should first recognise it as a national security threat that will open the possibility to increase defence spending, attract expertise and enhance multinational cooperation to combat this threat. Further, while deterrence frameworks such as the threat of sanctions might be effective in some cases, the main focus should be on humanities-based solutions to educate society. The example of Finland reveals an extraordinary level of informational resilience that was achieved primarily through this method. Therefore, educating society from a very young age about the informational literacy and dangers of disinformation is one of the most effective strategies that can help Western states significantly decrease the influence of this non-kinetic weapon.

Conclusion

As we can observe the threat of disinformation is a significant national security challenge that should not be considered as a mere inconvenience. Furthermore, Russia has a long-standing history and experience of implementing disinformation as part of its active measures and mastering the art of maskirovka in informational space. While a variety of literature exists on fighting disinformation among the current scholars, a majority tend to focus on fighting disinformation as a distinct entity rather than focusing on the intentions behind those campaigns by the state source which is crucial if we want to find the most effective strategies in combating Russian disinformation. Further, Russian tactics and strategic objectives have stayed relatively similar since the times of the Soviet Union up until this day. Tactics involve using true information such as an existing virus or a biolab and then adding on top of that deliberately false information that from the Kremlin’s perspective will help to achieve its objectives. Disinformation may start in various places such as Russian state-sponsored media or foreign media outlets with the main goal of reaching a Western audience. Moreover, as we can observe from the two case studies strategic objectives for Russia in most cases include justifying the invasion, creating disunity among NATO member states and partners, polarising Western societies and increasing the distrust towards governmental institutions among Western citizens. Therefore, achieving those objectives can help Russia in weakening Western states as highly polarised and disunited societies tend to be less effective when it comes to countering external threats. As the ancient Latin saying that is often attributed to Julius Caesar goes “divide and rule” (Athanasiou, 2024). However, while disinformation poses a substantial danger to Western states and is quite challenging to combat in contrast with conventional kinetic military threats, it can still be effectively tackled. In order to combat the influence of Russian disinformation Western states should first recognise it as a national security threat further opening a possibility to increase their defence spending focused on tackling this threat, attracting expertise and enhancing multinational cooperation. Further, an interesting approach could be the creation of informational deterrence through the threat of sanctions. Therefore, this approach is something that can be studied further. Furthermore, one of the most effective strategies is educating society about informational literacy and the threats of disinformation from a young age using the framework developed by Finland. Lastly, as we can observe in the second case study the current technologies-led solutions such as debunking proved to be ineffective, therefore, creating a resilient and critically thinking society through education is one of the most effective strategies in order to combat Russian disinformation.

Bibliography

Agursky, Mikhail (1989) “Soviet Disinformation And Forgeries”, International Journal on World Peace, Volume 6:1, 13-30.

Anonymous (1986) “Division X of the Hauptverwaltung Aufklärung (HVA/X) of the Ministry of State Security (MfS), ‘Plan for Common and Coordinated Active Measures of the Intelligence Organs of the MOI of the PR Bulgaria and the MfS of the GDR for 1987 and 1988’”, Wilson Center Digital Archive, September 3.

Anonymous (1987) “KGB, Information Nr. 2742 [to Bulgarian State Security]”, Wilson Center Digital Archive.

Anonymous (2016) “Gennady Onishchenko: US may be deliberately infecting mosquitoes with Zika virus”, RT, 16 February.

Ash, Lucy (2015) “How Russia outfoxes its enemies”, BBC News, January 29.

Athanasiou, Christina (2024) “Was Divide and Conquer a Julius Caesar Invention, or Not?”, Roman Empire Times, October 3.

Batiste, Dominique (2020) “Russia and Disinformation: Origins of Deception”, Panoply Journal, Volume 1.

Benkova Livia (2018) “The Rise of Russian Disinformation in Europe”, AIES, Volume 3.

Bernays, Edward (1928) “Propaganda”, (New York: Ig Publishing).

Borger, Julian and Rankin, Jennifer, et al (2022) “Russia makes claims of US-backed biological weapon plot at UN”, The Guardian, 11 March.

Brandt, Jessica and Wirtschafter, Valerie, et al (2022) “Popular podcasters spread Russian disinformation about Ukraine biolabs”, Brookings, 23 March.

Chamayou, Gregoire (2015) “Drone Theory” (London: Penguin Books).

Cull, Nicholas and Gatov, Vasily, et al (2017) “Soviet Subversion, Disinformation and Propaganda: How the West Fought Against it”, London School of Economics and Political Science, Volume 1.

Evon, Dan (2022) “Ukraine, US Biolabs, and an Ongoing Russian Disinformation Campaign”, Snopes, 24 February.

Fallis, Don (2009) “A Conceptual Analysis of Disinformation” (Arizona: ResearchGate).

Galeotti, Mark (2019) “Active Measures: Russia’s Covert Geopolitical Operations”, George C. Marshall Centre, June.

Gioe, David and Brinkworth, Robin, et al (2024) “Pairing Humanities With Technology to Combat Mis- and Disinformation”, Royal United Services Institute, Volume 6.

Henley, Jon (2020) “How Finland starts its fight against fake news in primary schools”, The Guardian, January 29.

Kello, Lucas (2017) “The Virtual Weapon and International Order” (Yale University Press).

Kirichenko, David (2024) “Military Lessons For NATO From The Russia-Ukraine War: Preparing For The Wars of Tomorrow”, The Henry Jackson Society, Volume 1.

Klepper, David and Knickmeyer, Ellen (2024) “Gabbard’s sympathetic views toward Russia cause alarm as Trump’s pick to lead intelligence services”, The Associated Press, 17 November.

Kofi, Annan (2006) “The address by UN Secretary-General Kofi Annan to the United Nations Association of the United Kingdom, Central Hall, Westminster, United Kingdom”, United Nations, 31 January, accessed at https://www.un.org/sg/en/content/sg/speeches/2006-01-31/address-un-secretary-general-kofi-annan-united-nations-association, 17 January 2025.

Lasswell, Harold, D. (1951) “The Strategy of Soviet Propaganda”, Proceedings of the Academy of Political Science, Volume 24: 2, 66–78.

Lentzos, Filippa (2018) “The Russian disinformation attack that poses a biological danger”, Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists, 19 November.

Lukes, Steven (2005) “Power: A Radical View”, 2nd edition (London: Red Globe Press).

Maier, Morgan (2016) “A Little Masquerade: Russia’s Evolving Employment of Maskirovka“, United States Army Command and General Staff College, Volume 1.

McGeehan, Timothy, P. (2018) “Countering Russian Disinformation”, Parameters, Volume 48:1.

Nietzsche, Friedrich (2019) “Beyond Good and Evil”, (Warsaw: Ktoczyta.pl).

Panayotov and Nikolov (1985) “KGB, Information Nr. 2955 [to Bulgarian State Security]”, Wilson Center Digital Archive, September 7.

Pearson, James and Landay, Jonathan (2022) “Cyberattack on NATO could trigger collective defence clause – official”, Reuters, February 28.

Pherson, Randolph H., and Mort Ranta, Penelope, et al (2020) “Strategies for Combating the Scourge of Digital Disinformation”, International Journal of Intelligence and CounterIntelligence, Vol. 34:2, 316–341.

Rising, David (2022) “China amplifies unsupported Russian claim of Ukraine biolabs”, The Associated Press, 11 March.

Selvage, Douglas (2022) “Moscow, ‘Bioweapons,’ and Ukraine: From Cold War ‘Active Measures’ to Putin’s War Propaganda”, Wilson Center, 22 March.

Selvage, Douglas and Nehring, Christopher (2019) “Operation ‘Denver’: KGB and Stasi Disinformation regarding AIDS”, Wilson Center, July 22.

Shu, Kai and Bhattacharjee, Amrita, et al (2020) “Combating disinformation in a social media age”, WIREs Data Mining Knowledge Discovery, Volume 1.

Splidsboel Hansen, Flemming (2017) “Russian hybrid warfare: A study of disinformation”, Danish Institute for International Studies, Volume 2017:06.

Thomas-Greenfield, Linda (2022) “Remarks by Ambassador Thomas-Greenfield at a UN Security Council Meeting on Russia’s Unfounded Allegations of Biological Weapons Programs in Ukraine”, United States Mission to the United Nations, 26 October.

Wike, Richard and Fagan, Moira, et al. (2024) “Views of Ukraine and U.S. involvement with the Russia-Ukraine war”, Pew Research Center, 8 May.

Zimmer, Phil (2013) “Maskirovka: The Hidden Key to Soviet Victory”, Warfare History Network, April.

Leave a comment